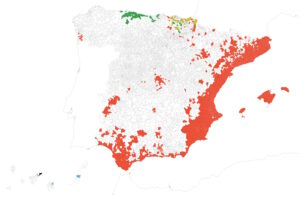

More than twenty years after the first detection of the tiger mosquito in Spain, a study published in the journal Insects presents for the first time a map of the distribution of three invasive species at the municipal level in the country. The work, which compiles two decades of surveillance and involved more than 40 authors, reveals that 1,813 of Spain’s 8,132 municipalities have already been colonized by one of these species.

This municipal distribution map has been made possible thanks to the collaboration of the scientific community, 33 academic institutions and public health agencies, as well as data contributed by citizens through the Mosquito Alert platform.

Twenty years of data and a pioneer hybrid model

The study analyses the expansion of three invasive species: the tiger mosquito, the yellow fever mosquito, and the Japanese mosquito (Aedes albopictus, Aedes aegypti, and Aedes japonicus, respectively) between 2004 and 2024. Led by Roger Eritja, Entomology and Data Validation Lead at Mosquito Alert and researcher at the Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC), and Frederic Bartumeus, co-director of Mosquito Alert, it brings together 42 specialists from 33 scientific and public health institutions, including the Ministry of Health.

The novelty of this map lies in the integration of multiple sources of information. On the one hand, it includes data obtained over 20 years of field surveillance through egg, larva, and adult sampling, carried out by the study’s authors, the regional governments, and the Ministry of Health. On the other hand, citizen contributions, 110,939 observations submitted by 33,183 people using the Mosquito Alert app, where mosquito photos are classified by a system that combines the speed of artificial intelligence with the accuracy of experts.

A model with remarkable results

In numbers, the study shows that over 20 years, invasive mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus, Aedes aegypti, Aedes japonicus) have been detected in 1,813 Spanish municipalities (22% of the total). The tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) is the most widespread and is present in 1,768 municipalities, including the most populated in the country, which means that two out of three people (66.2%) live exposed to its bites. As for the Japanese mosquito, discovered by Mosquito Alert in 2018, it has been detected in 111 municipalities in northern Spain, in 68 of which it co-occurs with the tiger. The yellow fever mosquito is, for now, restricted to introductions in the Canary Islands.

The project’s authors highlight that (since the last compilation in 2015) this is the first municipal-scale map to include citizen participation, which has contributed to one-third of detections in the country. Specifically, 24.6% of detections since 2014, and up to 31.8% when counting simultaneous findings with field sampling. Citizen science has enabled early detection of presence in 7 regions, including Andalusia, Galicia, Aragon, both Castiles, Cantabria, and Melilla. Data reveal that colonization first occurred in densely populated areas along the Mediterranean coast, later spreading inland.

Roger Eritja, first author of the study and CEAB-CSIC researcher, emphasizes that “field entomological surveillance is irreplaceable and can benefit from synergies with new technologies and strategies based on social cooperation. While field surveillance offers high accuracy, citizen science provides an early warning system with real-time, large-scale, low-cost data collection.”

Isis Sanpera, author of the study, member of Mosquito Alert, and researcher at Pompeu Fabra University, adds that “this hybrid and cooperative model is particularly useful to detect dispersal events beyond the known expansion front of the species.”

A global threat, a collective response

Mosquito Alert’s citizen science has established itself as a public health tool, being integrated into the National Plan for the Prevention, Surveillance, and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases by the Ministry of Health in 2023. This integration positions Spain as a pioneer in Europe in integrating citizen participation into official surveillance systems.

The combination of citizen science and professional sampling helps save costs, speed up early warnings, and strengthen outbreak prevention. This integrated approach provides a pioneering model of surveillance that is cost-effective, scalable, and adapted to the dynamics of invasive species and emerging epidemiological threats. “The challenge is to maintain citizen participation and involvement in the long term,” notes Sanpera, highlighting the importance of communication and collaboration between institutions and society.

Citizens can continue to support surveillance and research through Mosquito Alert by sending mosquito observations, thereby contributing to the work of the scientific community and health authorities in protecting public health.