The R+D CSIC magazine has interviewed Teresa Buchaca and Marc Ventura, researchers from CEAB-CSIC and scientific coordinators of this European project. Life Resque Alpyr aims to recover mountain aquatic habitats by improving the conservation of various habitats and target species in four Natura 2000 sites in the Pyrenees and the Alps.

(below, the interview published on October 28 in R+D CSIC, conducted by Marina Prado Utrilla, Comunicació CSIC Catalunya, is reproduced)

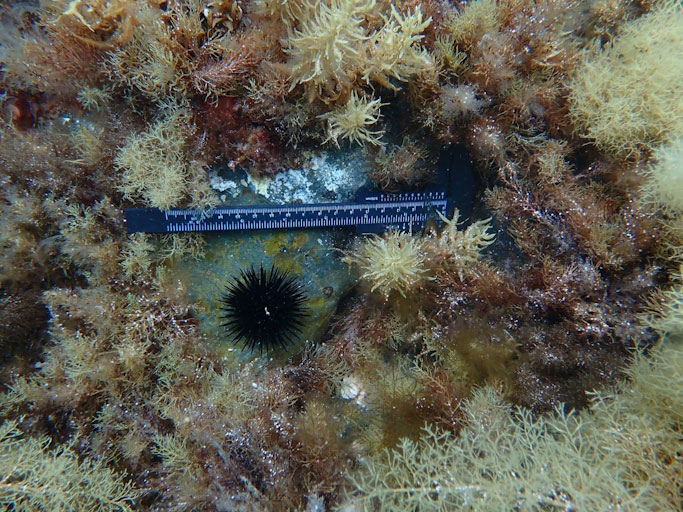

The Life Resque Alpyr project, coordinated by the Centre for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC), has been working for years to restore high mountain aquatic habitats. The goal is to convert the intervened lakes into reservoirs of biodiversity and ecological corridors, for which they carry out different types of actions. One of them is to control the presence of exotic and, in many cases, invasive species, which reduce the diversity of native species and alter the balance of the ecosystem. This happens with the minnowfish (Phoxinus spp.), a fast-growing, high-reproductive fish that has high adaptability and forms dense populations.

The conventional capture techniques used so far are not effective for this species, so two pilot tests have been carried out with rotenone, a biodegradable chemical extracted from leguminous plants. Its use was already known in areas of Norway and the United States, but these actions are pioneering in the context of high mountains in Europe. They are still analyzing the results, which will provide crucial data to evaluate the efficacy and safety of this product.

One intervention took place in 2024 on Lake Manhèra (Val d’Aran), and two have been in September of this year 2025, in the Tres Estanys area: a first on Lake Tres Estanys del Mig and, a few weeks later, on Lake Tres Estanys de Baix.

To learn a little more about these processes, we have interviewed Teresa Buchaca and Marc Ventura, scientific coordinators of the project.

What is the quantitative difference between conventional techniques, such as nets, traps and fishing, with respect to rotenone?

The main difference is time, which in the end also entails a higher economic cost. To eliminate the minnowfish using conventional techniques, we need between 4 and 7 years of continuous fishing effort, while with rotenone the effort is one day of treatment. In terms of cost, it is approximately 30% cheaper.

How exactly does the introduction of the chemical work? Because in addition to fish, there are other species in a lake, doesn’t it affect them?

Yes, it would affect them, as rotenone has an inhibitory effect on gill respiration. Any organism that breathes through gills will be affected, but fish are the group of organisms most sensitive to this product. Even so, we must bear in mind that the application of this product is only carried out in lakes where unfortunately there are no amphibians or other fauna that can be put at risk. Only small invertebrates remain and we have found that they are capable of recovering their populations.

Is the procidure carried out in places where there’s only presence of the exotic species, or can rotenone also be used in lakes where there are other types of fish? How do you do it in this case, so that the native species doesn’t become intoxicated with rotenone?

In the Pyrenees it has only been applied where there is minnow, which is the exotic species, and invasive in this case. But in 2022 we participated in a follow-up that was carried out after the application of rotenone in two small coastal lagoons, near Ametlla de Mar, in Tarragona, where there are populations of samaruc [a species whose scientific name is Hispanic Valencia]. It is a fish that is only found in a few lagoons in the eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula and faces a critical state of conservation after the introduction of the gambusia [Gambusia holbrooki]. Gambusia is native to the southeastern United States and was introduced in the early 20th century to help controling mosquito larvae during anti-malaria campaigns.

In this case we had to previously capture as many specimens as possible of the protected species, the samaruc, to keep it in captivity in the facilities of the Ebro Delta Natural Park. We were then able to release them after we had applied rotenone and it had completely degraded.

How do you choose where to use rotenone so that it doesn’t spread through water or soil? It is a natural biodegradable ichthyocide. How long does it take to degrade? Does it affect other species during that time?

Let’s say that there are a number of considerations to take into account when deciding where it can be applied. First, it is checked that the ecosystem where it operates is sufficiently disturbed to intervene, and that it corresponds to a location where eradication with mechanical methods is not considered viable. A second point is that the lake cannot be recolonized again by fish. Meeting these conditions, the next thing to take into account has to do with the application of the product. On the one hand, in terms of application success, which involves studying the properties of the water to calculate the appropriate application dose of the product. And, on the other hand, in terms of safety, to prevent the product from leaving the area where the action will be carried out. In this sense, in the pilot applications carried out in the Pyrenees, there has always been a lake below the area of action that could act as a natural plugger of the system.

Regarding its behavior in the environment, it is not a persistent compound since it degrades quickly, resulting in waste that is no longer toxic and that disappears from the environment in a few days, at most a few weeks. Because it is biodegradable, there is no risk that it can accumulate in food webs, and as the application dose is very low, it doesn’t pose a risk to humans or livestock.

Rotenone is not a persistent compound since it degrades quickly, resulting in waste that is no longer toxic and that disappears from the environment in a few days, at most a few weeks

From which plants is rotenone extracted? Because, as you explained, it was already traditionally used with different species, depending on the area, also in the Pyrenees.

Centuries ago, toxic plants were already used for fishing in some villages, also in the Pyrenees. We have found quotes about it in the Zamora questionnaire, which was a set of questions prepared by Francisco de Zamora in 1789 to collect detailed information about Catalonia. It told how people stiffened the waters to catch fish. That is, they used toxic plants such as mullein (Verbascum spp.), locally called ‘gamó’, which in this case contains saponins, a compound that interferes with the absorption of oxygen in the gills and produced a narcotic effect on fish. That way they could capture them more easily. In addition to this plant, others used for this purpose include plants of the legume family, of the genera Derris, Lonchocarpus, and Tephrosia, which contain rotenone.

How did you come up with the idea of trying rotenone in Spain? How did you intervene before the natural enclaves that suffered from this problem?

It was due to the need to restore lakes of greater size and complexity. The first restoration measures began using mechanical fishing methods. Specifically within the framework of two projects of the LIFE conservation programme, funded by the European Union. One is LIFE BioAquae, in the Alps, which was the first to achieve the eradication of salmonids in high mountain lakes in Europe. Then, with LIFE+ LimnoPirineus, coordinated by CEAB-CSIC, with which we managed to eradicate the minnowfish from high mountain lakes in the Pyrenees, something that had not been attempted before. But in both cases it was through the use of conventional mechanical methods such as nets, traps and electric fishing.

Here it became clear that these conventional techniques do not always give satisfactory results when there is piscardo, especially in larger lakes or lakes of greater ecological complexity. So the need to explore alternative methods was confirmed. We were aware of the use of rotenone for the elimination of invasive fish in other aquatic environments and other countries, and it was considered that it could be an interesting option to try within the framework of LIFE projects, which precisely seek to finance demonstration projects that apply actions in new contexts.

Although it is necessary to continue long-term ecological monitoring to certify the results, everything indicates that in both it has been a success and has managed to eradicate the piscardo

Where do you plan your next intervention with rotenone in the Pyrenees?

At the moment, no more intervention is planned in the Pyrenees, the two planned ones have already been carried out, which were in Lake Manhera in 2024 and in the Tres Estanys Mig and Tres Estanys de Baix lakes, last September. Although it is necessary to continue long-term ecological monitoring to certify the results, everything indicates that in both it has been a success and has managed to eradicate the piscardo.

In which other territories of the peninsula would rotenone be applicable? Or does it only work on terrain with these characteristics? Because I imagine that exotic fish must be in many other natural places.

Rotenone has been applied in Spain on a couple of occasions in low-altitude areas, and in other countries such as Norway or the United States it is being applied at entire basin scales. But this type of action requires a great deal of planning and in many cases may not make sense, especially if there is a risk of subsequent reintroductions.

Have you had any technical or social difficulties when it came to the application?

The technical difficulties, after having the Health permits and having the application approved, have been mainly of a logistical nature. Due to the remote location of the lakes, situated at 2,300 (Lake Manhèra) and 2,400m altitude (the Tres Estanys lake system), they are only accessible on foot or by air. It has been necessary to set up a large device to move all the necessary material by helicopter.

From a social point of view, before the application for the project, the actions were agreed with the administrations involved, at a national, regional and local level. In the case of the application in the Tres Estanys lake system, some social concern was generated, especially among the residents of the town closest to the intervention. But informative meetings were held and complementary measures were applied, such as the distribution of bottled water for their peace of mind.

How is the iNaturalist app working and the goal of engaging volunteers and citizen science?

In June 2024, the project’s profile was officially launched on the iNaturalist platform. The aim is to involve society in the collection of data on flora and fauna in high mountain aquatic ecosystems in the Alps and Pyrenees area. The number of direct followers is not yet very high, but it is a very valuable tool. Thanks to the collaborative structure of the platform, the profile benefits from the open data published by the large number of users who contribute their observations within the geographical scope and delimited species. And this has allowed us to gain a wealth of information about the distribution of our target species.

About the project

The Life Resque Alpyr project is co-funded by the European Union’s LIFE 2020 programme, which promotes conservation and recovery actions for habitats and species of flora and fauna in protected areas within the European Natura 2000 network. It is coordinated by the Centre for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC). The actions to eliminate the fish, both using mechanical methods and the application of rotenone, have been carried out under the technical direction of the company Sorelló Estudis al Medi Aquàtic. The Institute of Environmental Diagnosis and Water Studies (IDAEA-CSIC) has been responsible for quantifying the degradation of rotenone. In the Catalan part of the project, the Department of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Food of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Conselh Generau d’Aran, the University of Barcelona, the Catalan Forest Company, and the La Sorelona Association also participate as partners. The Andrena Foundation and the municipalities of Espot and Lladorre also participate as co-financiers.